Eight people die in the London Beer Flood.

Late on the Monday afternoon of October 17, 1814, distraught Anne Saville mourned over the body of her 2-year-old son, John, who had died the previous day. In her cellar apartment in London’s St. Giles neighborhood, fellow Irishwomen offered comfort as they waked the small boy and awaited the arrival of their husbands and sons who toiled in grueling manual labor jobs around the city. Upstairs on the first floor of the cramped New Street tenement, Mary Banfield sat down for tea with her 4-year-old daughter, Hannah. Behind the Tavistock Arms public house on nearby Great Russell Street, 14-year-old servant Eleanor Cooper scoured pots at the outdoor water pump in the shadow of a 25-foot-high brick wall.

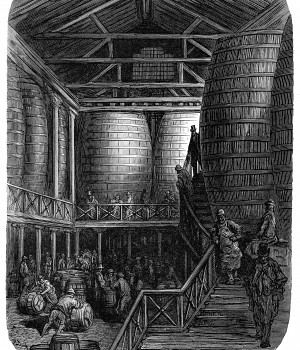

On the other side of the soaring barrier stood the extensive Bainbridge Street brewery of Messrs. Henry Meux and Co., which dominated the Irish enclave. Founded early in the reign of King George III and famous for its porter, the brewery produced more than 100,000 barrels of the dark-colored nectar each year.

Only two days after the catastrophe, a jury convened to investigate the accident. After visiting the site of the tragedy, viewing the bodies of the victims and hearing testimony from Crick and others, the jury rendered its verdict that the incident had been an “Act of God” and that the victims had met their deaths “casually, accidentally and by misfortune.” Not only did the brewery escape paying damages to the destitute victims, it received a waiver from the British Parliament for excise taxes it had already paid on the thousands of barrels of beer it lost.