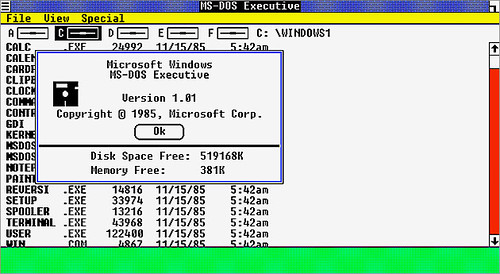

Bill Gates introduces Windows 1.0.

Tag Archives: 1983

6 May 1983

The Hitler Diaries are revealed as a hoax after being examined by experts.

[rdp-wiki-embed url=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hitler_Diaries’]

11 March 1983

Bob Hawke is appointed Prime Minister of Australia.

[rdp-wiki-embed url=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_Hawke’]

19 January 1983

Nazi war criminal Klaus Barbie is arrested in Bolivia.

[rdp-wiki-embed url=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klaus_Barbie’]

2 November 1983

U.S. President Ronald Reagan signs a bill creating Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.

12 April 1983

Harold Washington is elected as the first black mayor of Chicago.

Harold Lee Washington, April 15, 1922 – November 25, 1987 was an American lawyer and politician who was the 51st Mayor of Chicago. Washington became the first African–American to be elected as the city’s mayor in February 1983. He served as mayor from April 29, 1983 until his death on November 25, 1987. Earlier, he was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1981 to 1983, representing Illinois’ first district. Washington had previously served in the Illinois State Senate and the Illinois House of Representatives from 1965 until 1976.

Harold Lee Washington, April 15, 1922 – November 25, 1987 was an American lawyer and politician who was the 51st Mayor of Chicago. Washington became the first African–American to be elected as the city’s mayor in February 1983. He served as mayor from April 29, 1983 until his death on November 25, 1987. Earlier, he was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1981 to 1983, representing Illinois’ first district. Washington had previously served in the Illinois State Senate and the Illinois House of Representatives from 1965 until 1976.

Washington was born in Chicago, and raised in the Bronzeville neighborhood. After graduating from Roosevelt University and Northwestern University School of Law, he became involved in local 3rd Ward politics under future Congressman Ralph Metcalfe.

The earliest known ancestor of Harold Lee Washington, Isam/Isham Washington, was born a slave in 1832 in North Carolina. In 1864 he enlisted in the 8th United States Colored Heavy Artillery, Company L, in Paducah, Kentucky. Following his discharge in 1866, he began farming with his wife Rebecca Neal in Ballard County, Kentucky. Among their six children was Isam/Isom McDaniel Washington, who was born in 1875. In 1896, Mack Washington had married Arbella Weeks of Massac County, who had been born in Mississippi in 1878. In 1897, their first son, Roy L. Washington, father of Mayor Washington was born in Ballard County, Kentucky. In 1903, shortly after both families moved to Massac County, Illinois, the elder Washington died. After farming for a time, Mack Washington became a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, serving numerous churches in Illinois until the death of his wife in 1952. Reverend I.M.D. Washington died in 1953.

Harold Lee Washington was born on April 15, 1922 at Cook County Hospital in Chicago, Illinois, to Roy and Bertha Washington. While still in high school in Lawrenceville, Illinois, Roy met Bertha from nearby Carrier Mills and the two married in 1916 in Harrisburg, Illinois. Their first son, Roy Jr., was born in Carrier Mills before the family moved to Chicago where Roy enrolled in Kent College of Law. A lawyer, he became one of the first black precinct captains in the city, and a Methodist minister. In 1918, daughter Geneva was born and second son Edward was born in 1920. Bertha left the family, possibly to seek her fortune as a singer, and the couple divorced in 1928. Bertha remarried and had seven more children including Ramon Price, who was an artist and eventually became chief curator of The DuSable Museum of African American History. Harold Washington grew up in Bronzeville, a Chicago neighborhood that was the center of black culture for the entire Midwest in the early and middle 20th century. Edward and Harold stayed with their father while Roy Jr and Geneva were cared by grandparents. After attending St Benedict the Moor Boarding School in Milwaukee from 1928 to 1932, Washington attended DuSable High School, then a newly established racially segregated public high school, and was a member of its first graduating class. In a 1939 citywide track meet, Washington placed first in the 110 meter high hurdles event, and second in the 220 meter low hurdles event. Between his junior and senior year of high school, Washington dropped out, claiming that he no longer felt challenged by the coursework. He worked at a meat-packing plant for a time before his father helped him get a job at the U.S. Treasury branch in the city. There he met Nancy Dorothy Finch, whom he married soon after; Washington was 19 years old and Dorothy was 17 years old. Seven months later, the U.S. was drawn into World War II with the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese on Sunday, December 7, 1941.

25 October 1983

The United States invades Grenada, six days after Prime Minister Maurice Bishop and several of his supporters are executed in a coup.

The United States invasion of Grenada began on 25 October 1983. The invasion, led by the United States, of the Caribbean island nation of Grenada, which has a population of about 91,000 and is located 160 kilometres north of Venezuela, resulted in a U.S. victory within a matter of days. Codenamed Operation Urgent Fury, it was triggered by the internal strife within the People’s Revolutionary Government that resulted in the house arrest and the execution of the previous leader and second Prime Minister of Grenada Maurice Bishop, and the establishment of a preliminary government, the Revolutionary Military Council with Hudson Austin as Chairman. The invasion resulted in the appointment of an interim government, followed by democratic elections in 1984. The country has remained a democratic nation since then.

Grenada gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1974. The Marxist-Leninist New Jewel Movement seized power in a coup in 1979 under Maurice Bishop, suspending the constitution and detaining a number of political prisoners. In 1983, an internal power struggle began over Bishop’s relatively moderate foreign policy approach, and on 19 October, hard-line military junta elements captured and executed Bishop and his partner Jacqueline Creft, along with three cabinet ministers and two union leaders. Subsequently, following appeals by the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States and the Governor-General of Grenada, Paul Scoon, the Reagan Administration in the U.S. quickly decided to launch a military intervention. U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s justification for the intervention was in part explained as “concerns over the 600 U.S. medical students on the island” and fears of a repeat of the Iran hostage crisis.

The U.S. invasion began six days after Bishop’s death, on the morning of 25 October 1983. The invading force consisted of the U.S. Army’s Rapid Deployment Force; U.S. Marines; U.S. Army Delta Force; U.S. Navy SEALs, and ancillary forces totaling 7,600 U.S.troops, together with Jamaican forces, and troops of the Regional Security System. They defeated Grenadian resistance after a low-altitude airborne assault by Rangers on Point Salines Airport at the south end of the island, and a Marine helicopter and amphibious landing on the north end at Pearls Airport. The military government of Hudson Austin was deposed and replaced by a government appointed by Governor-General Paul Scoon.

The invasion was criticised by several countries including Canada. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher privately disapproved of the mission and the lack of notice she received, but publicly supported the intervention. The United Nations General Assembly, on 2 November 1983 with a vote of 108 to 9, condemned it as “a flagrant violation of international law”. Conversely, it enjoyed broad public support in the United States and, over time, a positive evaluation from the Grenadian population, who appreciated the fact that there had been relatively few civilian casualties, as well as the return to democratic elections in 1984 better source needed The U.S. awarded more than 5,000 medals for merit and valor.

The date of the invasion is now a national holiday in Grenada, called Thanksgiving Day, which commemorates the freeing, after the invasion, of several political prisoners who were subsequently elected to office. A truth and reconciliation commission was launched in 2000 to re-examine some of the controversies of the era; in particular, the commission made an unsuccessful attempt to find Bishop’s body, which had been disposed of at Hudson Austin’s order, and never found.

For the U.S., the invasion also highlighted issues with communication and coordination between the different branches of the United States military when operating together as a joint force, contributing to investigations and sweeping changes in the form of the Goldwater-Nichols Act and other reorganizations.

6 May 1983

The Hitler Diaries are reported as being a hoax after being examined by experts.

On 22 April 1983 a press release from Stern announced the existence of the diaries and their forthcoming publication; a press conference was announced for 25 April. On hearing the news from Stern, Jäckel stated that he was “extremely sceptical” about the diaries, while his fellow historian, Karl Dietrich Bracher of the University of Bonn also thought their legitimacy unlikely. Irving was receiving calls from international news companies—the BBC, The Observer, Newsweek, Bild Zeitung—and he was informing them all that the diaries were fakes. The German Chancellor, Helmut Kohl, also said that he could not believe the diaries were genuine, the following day The Times published the news that their Sunday sister paper had the serialisation rights for the UK; the edition also carried an extensive piece by Trevor-Roper with his opinion on the authenticity and importance of the discovery. By this stage the historian had growing doubts over the diaries, which he passed on to the editor of The Times, Charles Douglas-Home, the Times editor presumed that Trevor-Roper would also contact Giles at The Sunday Times, while Trevor-Roper thought that Douglas-Home would do so; neither did. The Sunday paper thus remained oblivious of the growing concerns that the diaries might not be genuine.

On the evening of 23 April the presses began rolling for the following day’s edition of The Sunday Times, after an evening meeting of the editorial staff, Giles phoned Trevor-Roper to ask him to write a piece rebutting the criticism of the diaries. He found that the historian had made “a 180 degree turn” regarding the diaries’ authenticity, and was now far from sure that they were real. The paper’s deputy editor, Brian MacArthur, rang Murdoch to see if they should stop the print run and re-write the affected pages. Murdoch’s reply was “Fuck Dacre. Publish”.

On the afternoon of the 24 April, in Hamburg for the press conference the following day, Trevor-Roper asked Heidemann for the name of his source: the journalist refused, and gave a different story of how the diaries had been acquired. Trevor-Roper was suspicious and questioned the reporter closely for over an hour. Heidemann accused the historian of acting “exactly like an officer of the British army” in 1945, at a subsequent dinner the historian was evasive when asked by Stern executives what he was going to say at the announcement the following day.

At the press conference both Trevor-Roper and Weinberg expressed their doubts at the authenticity, and stated that German experts needed to examine the diaries to confirm whether the works were genuine. Trevor-Roper went on to say that his doubts sprung from the lack of proof that these books were the same ones as had been on the crashed plane in 1945, he finished his statement by saying that “I regret that the normal method of historical verification has been sacrificed to the perhaps necessary requirements of a journalistic scoop.” The leading article in The Guardian described his public reversal as showing “moral courage”. Irving, who had been described in the introductory statement by Koch as a historian “with no reputation to lose”, stood at the microphone for questions, and asked how Hitler could have written his diary in the days following the 20 July plot, when his arm had been damaged, he denounced the diaries as forgeries, and held aloft the photocopied pages he had been given from Priesack. He asked if the ink in the diaries had been tested, but there was no response from the managers of Stern. Photographers and film crews jostled to get a better picture of Irving, and some punches were thrown by journalists while security guards moved in and forcibly removed Irving from the room, while he shouted “Ink! Ink!”.

With grave doubts now expressed about the authenticity of the diaries, Stern faced the possibility of legal action for disseminating Nazi propaganda. To ensure a definitive judgment on the diaries, Dr Hagen, one of the company’s lawyers, passed three complete diaries to Dr Henke at the Bundesarchiv for a more complete forensic examination. While the debate on the diaries’ authenticity continued, Stern published its special edition on 28 April, which provided Hitler’s purported views on the flight of Hess to England, Kristallnacht and the Holocaust. The following day Heidemann again met with Kujau, and bought the last four diaries from him.

On the following Sunday—1 May 1983—The Sunday Times published further stories providing the background to the diaries, linking them more closely to the plane crash in 1945, and providing a profile of Heidemann, that day, when The Daily Express rang Irving for a further comment on the diaries, he informed them that he now believed the diaries to be genuine; The Times ran the story of Irving’s U-turn the following day. Irving explained that Stern had shown him a diary from April 1945 in which the writing sloped downwards from left to right, and the script of which got smaller along the line, at a subsequent press conference Irving explained that he had been examining the diaries of Dr Theodor Morell, Hitler’s personal doctor, in which Morell diagnosed the Führer as having Parkinson’s disease, a symptom of which was to write in the way the text appeared in the diaries. Harris posits that further motives may also have played a part—the lack of reference to the Holocaust in the diaries may have been perceived by Irving as supporting evidence for his thesis, put forward in his book Hitler’s War, that the Holocaust took place without Hitler’s knowledge, the same day Hagen visited the Bundesarchiv and was told of their findings: ultraviolet light had shown a fluorescent element to the paper, which should not have been present in an old document, and that the bindings of one of the diaries included polyester which had not been made before 1953. Research in the archives also showed a number of errors, the findings were partial only, and not conclusive; more volumes were provided to aid the analysis.

Genuine signature of Adolf Hitler

Forged version of Hitler’s signature, showing slight differences from the original

Kujau’s version of Hitler’s signature, which Kenneth W. Rendell described as a “terrible rendition”.

When Hagen reported back to the Stern management, an emergency meeting was called and Schulte-Hillen demanded the identity of Heidemann’s source, the journalist relented, and provided the provenance of the diaries as Kujau had given it to him. Harris describes how a bunker mentality descended on the Stern management as, instead of accepting the truth of the Bundesarchiv’s findings, they searched for alternative explanations as to how post-war whitening agents could have been used in the wartime paper. The paper then released a statement defending their position which Harris judges was “resonant with hollow bravado”.

While Koch was touring the US, giving interviews to most of the major news channels, he met Kenneth W. Rendell, a handwriting expert in the studios of CBS, and showed him one of the volumes. Rendell’s first impression was that the diaries were forged, he later reported that “everything looked wrong”, including new-looking ink, poor quality paper and signatures that were “terrible renditions” of Hitler’s. Rendell concludes the diaries were not particularly good fakes, calling them “bad forgeries but a great hoax”, he states that “with the exception of imitating Hitler’s habit of slanting his writing diagonally as he wrote across the page, the forger failed to observe or to imitate the most fundamental characteristics of his handwriting.”

On 4 May fifteen volumes of the diaries were removed from the Swiss bank vault and distributed to various forensic scientists: four went to the Bundesarchiv and eleven went to the Swiss specialists in St Gallen, the initial results were ready on 6 May, which confirmed what the forensic experts had been telling the management of Stern for the last week: the diaries were poor forgeries, with modern components and ink that was not in common use in wartime Germany. Measurements had been taken of the evaporation of chloride in the ink which showed the diaries had been written within the previous two years. There were also factual errors, including some from Domarus’s Hitler: Reden und Proklamationen, 1932–45 that Kujau had copied. Before passing the news to Stern, the Bundesarchiv had already informed the government, saying it was “a ministerial matter”, the managers at Stern tried to release the first press statement that acknowledged the forensic findings and stated that the diaries were forged, but the official government announcement was released five minutes before Stern’s.

10 November 1983

Bill Gates announces Windows 1.0.

Microsoft chief Bill Gates unveils the Windows operating system for PCs. Don’t hold your breath waiting until you can buy a copy … unless you can hold your breath for two years.

Gates, Microsoft’s president and board chairman, held an elaborate event at New York City’s posh Helmsley Palace Hotel. The debutante at this ball was an operating system with a graphical user interface.

A History of Microsoft Windows Photo Gallery

BSOD Through the AgesIf you were struggling with the arcane and unfriendly MS-DOS, you were ready to get something that was easier to drive. Typing commands at the C prompt may have been a piece of C:\ake for programmers and geeks, but it was a pain in the wrist for the run-of-the-mill office chair jockey.

Microsoft started working on a product first called Interface Manager in September 1981. Early prototypes used MS Word-style menus at the bottom of the screen. That changed to pulldown menus and dialogs (a la Xerox Star) in 1982.

By 1983, Microsoft was facing competition from the just-released VisiOn and the forthcoming TopView. Apple had already released Lisa, but Digital’s GEM, Quarterdeck’s DESQ, the Amiga Workbench, IBM OS/2 and Tandy DeskMate were all still in the future.

18 June 1983

The astronaut Sally Ride becomes the first American woman in space.

One of six women selected in NASA’s 1978 astronaut class, Sally Ride was the first of them to fly. When she rode aboard the space shuttle Challenger as it lifted off from Kennedy Space Center on June 18, 1983, she became the first American woman in space and captured the nation’s attention and imagination as a symbol of the ability of women to break barriers. As one of the three mission specialists on the STS-7 mission, she played a vital role in helping the crew deploy communications satellites, conduct experiments and make use of the first Shuttle Pallet Satellite. Her pioneering voyage and remarkable life helped, as President Barack Obama said soon after her death last summer, “inspire generations of young girls to reach for the stars” for she “showed us that there are no limits to what we can achieve.”

Sally Ride was born in Los Angeles, California, on May 26, 1951. Fascinated by science from a young age, she pursued the study of physics, along with English, in school. As she was graduating from Stanford University with a Ph.D. in physics, having done research in astrophysics and free electron laser physics, Ride noticed a newspaper ad for NASA astronauts. She turned in an application, along with 8,000 other people, and was one of only 35 chosen to join the astronaut corps. Joining NASA in 1978, she served as the ground-based capsule communicator, or capcom, for the second and third space shuttle missions and helped with development of the space shuttle’s robotic arm.After her selection for the crew of STS-7, and thereby becoming the first American woman in space, Ride faced intense media attention.