The Cuban Missile Crisis ends.

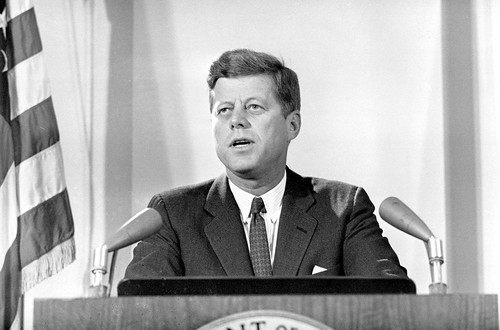

President Kennedy called on Premier Khrushchev tonight to carry out his promised missile pullback “at once” so that the U.S. and Russia could move promptly “to the settlement of the Cuban crisis.”

Officials disclosed that the U.S. would insist on a time line in the UN negotiations on pullout details. Informed sources said it should be a “very, very short” period, a matter of days, because some of the missiles already are operational.

In a new letter to the Kremlin leader the President declared that he now believed he and Khrushchev had reached “firm” agreement on the terms for ending an ominous East-West clash that had carried the world to the brink of nuclear war.

In return for a speedy missile pullback in Cuba, under UN supervision, the President said the U.S. would lift the sea blockade and offer Russia assurances against a Cuban invasion.

“I hope that the necessary measures can at once be taken through the United Nations, as your message says,” Kennedy told Khrushchev, “so that the U.S. in turn will be able to remove the quarantine measures now in effect.”

In a separate gesture to smooth the path to a final settlement the President voiced “regret” that an American plane collecting fallout samples in the atmosphere had slipped into Soviet air space in far northeast Siberia. He promised that “every precaution” would be taken to prevent a recurrence.

Kennedy’s letter was made public less than eight hours after the Moscow radio broadcast a Khrushchev letter agreeing to Kennedy’s missile pullout demands. It seemed to mark the beginning of the end of the fateful cold war collision.

Around the world the news brought a sigh of relief despite Administration attempts to ward off any premature victory statements.

Even Kennedy suggested in his letter that a solution was at hand. Underlining this was the fact that Kennedy spent the first afternoon away from his desk since the crisis erupted.